Inspired by living things from trees to shellfish, researchers at The University of Texas at Austin set out to create a plastic much like many life forms that are hard and rigid in some places and soft and stretchy in others. Their success—a first, using only light and a catalyst to change properties such as hardness and elasticity in molecules of the same type—has brought about a new material that is 10 times as tough as natural rubber and could lead to more flexible electronics and robotics.

The findings are published today in the journal Science.

“This is the first material of its type,” said Zachariah Page, assistant professor of chemistry and corresponding author on the paper. “The ability to control crystallization, and therefore the physical properties of the material, with the application of light is potentially transformative for wearable electronics or actuators in soft robotics.”

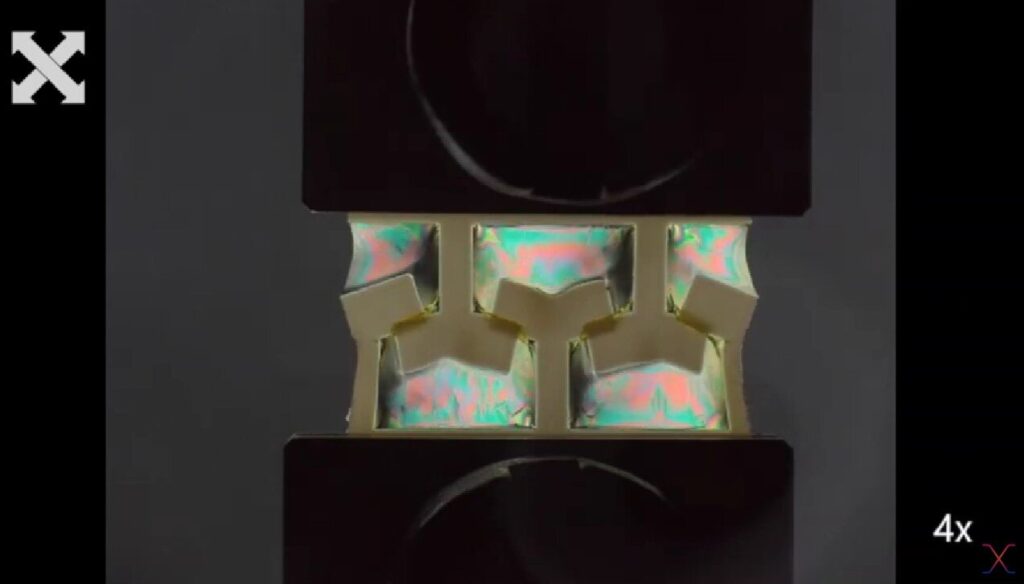

Patterned sample is being stretched under uniaxial tension. Video was recorded with the sample between cross-polarizers, allowing for visualization of polymer chain alignment. The dark, opaque sections have been hardened. The transparent sections have been left soft and stretchy. Credit: The University of Texas at Austin

Scientists have long sought to mimic the properties of living structures, like skin and muscle, with synthetic materials. In living organisms, structures often combine attributes such as strength and flexibility with ease. When using a mix of different synthetic materials to mimic these attributes, materials often fail, coming apart and ripping at the junctures between different materials.

Oftentimes, when bringing materials together, particularly if they have very different mechanical properties, they want to come apart,” Page said. Page and his team were able to control and change the structure of a plastic-like material, using light to alter how firm or stretchy the material would be.

Patterned island sample is being stretched and relaxed under uniaxial tension. Video was recorded with the sample as seen (left) and between cross-polarizers (right), allowing for visualization of polymer chain alignment. The dark, opaque spots are areas that have been hardened. Credit: The University of Texas at Austin

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Chemists started with a monomer, a small molecule that binds with others like it to form the building blocks for larger structures called polymers that were similar to the polymer found in the most commonly used plastic. After testing a dozen catalysts, they found one that, when added to their monomer and shown visible light, resulted in a semicrystalline polymer similar to those found in existing synthetic rubber. A harder and more rigid material was formed in the areas the light touched, while the unlit areas retained their soft, stretchy properties.

Because the substance is made of one material with different properties, it was stronger and could be stretched farther than most mixed materials.

The reaction takes place at room temperature, the monomer and catalyst are commercially available, and researchers used inexpensive blue LEDs as the light source in the experiment. The reaction also takes less than an hour and minimizes use of any hazardous waste, which makes the process rapid, inexpensive, energy efficient and environmentally benign.

The researchers will next seek to develop more objects with the material to continue to test its usability.

“We are looking forward to exploring methods of applying this chemistry towards making 3D objects containing both hard and soft components,” said first author Adrian Rylski, a doctoral student at UT Austin.

The team envisions the material could be used as a flexible foundation to anchor electronic components in medical devices or wearable tech. In robotics, strong and flexible materials are desirable to improve movement and durability.

Henry L. Cater, Keldy S. Mason, Marshall J. Allen, Anthony J. Arrowood, Benny D. Freeman and Gabriel E. Sanoja of The University of Texas at Austin also contributed to the research.